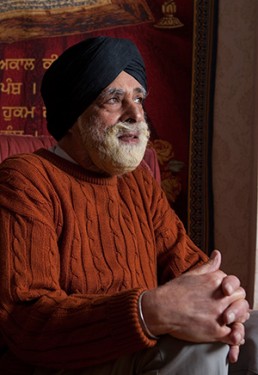

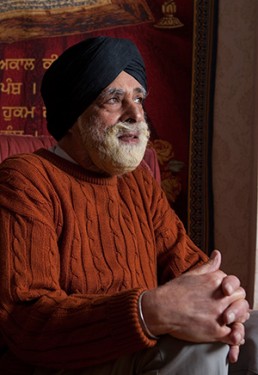

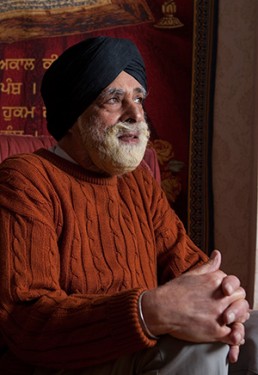

LONDON, UK—Lord Singh is widely known for his contributions to the “Thought for the Day” slot on BBC Radio 4, urging religious tolerance in gentle, measured tones, but his influence extends far beyond the breakfast table. This tireless campaigner is currently demanding an apology from the British government over its possible involvement – revealed this week – in the 1984 attack by the Indian government on the Sikh temple at Amritsar.

A practising Sikh, Singh co-founded the Inter Faith Network for the UK in 1987 to promote better relations between religions, and in 2008 he became the first Sikh to address a major conference at the Vatican. He set up the Network of Sikh Organisations in 1995, co-ordinating pastoral care for Sikhs in hospitals, prisons and the armed forces. The Prince of Wales, Anglican bishops and the Metropolitan Police are among those who have consulted him, and he has advised the government on race relations. In 2011, he was made a crossbench life peer in the House of Lords – the first member to wear a turban.

Born Indarjit Singh in 1932 in Rawalpindi, now in Pakistan, he moved to the UK as a baby. Singh’s father, a doctor, had been involved in the Indian independence movement and was “virtually exiled” to east Africa; after studying in Britain he decided to move his family there rather than returning to India. So, in 1933, Singh, together with his two elder brothers and mother, joined his father in Birmingham.

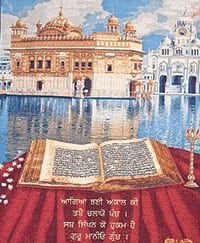

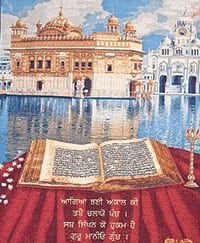

Singh now lives in the detached Victorian house in Wimbledon, southwest London, that he and his wife, Kanwaljit, bought in 1974. Forty years after the Singhs moved in with their two young daughters, the home feels lived-in but well-maintained, and various decorative objects attest to the couple’s broad tastes: an engraving of the Golden Temple in Amritsar, north India, the holiest Sikh shrine; an ancient Greek-style plate; a painted Alpine scene; and a Japanese print.

Singh met his wife in India, when he was working there as a mine engineer, and they moved to England in the mid-1960s – first to Birmingham, then London when Singh was offered a job in civil engineering. He later studied for an MBA and moved into local government. Kanwaljit, in turn, has worked as a primary schoolteacher, a headteacher and a school inspector. In 2011 she was awarded an OBE for services to education and interfaith understanding.

Over tea and homemade samosas, Singh recalls his childhood in Birmingham – where, in 1939, the Indian population was estimated at just 100. “My parents had a very tough time. They wouldn’t give my father a hospital job so he set up his own practice as a GP. He was a very determined chap, but the patients didn’t come too quickly. My mother even had to pawn some of her jewellery for things like bread and milk.” At this, he breaks into laughter, his eyes almost disappearing as his face creases. “But they came through it all, and the practice grew and grew.”

Singh is serious in his beliefs but quick to laugh at life’s absurdities – even the absurdity of prejudice. The Singh brothers were the only non-white pupils at the local grammar school. “Everyone knew that Britain was top and everybody else was down there,” he gestures to the floor. “There was a history teacher who looked directly at me in class and said ‘They come over here, they get educated and they go back to India to harass us’.” Did that upset him? “No,” he says, “it was par for the course. We knew it was wrong but it was the game being played. It was snakes and ladders and your ladders had broken rungs.”

After graduating from Birmingham university in 1959 with a first-class degree in engineering, Singh applied to the Coal Board to become a mine manager. However, at his interview he was squarely informed that “miners in this country wouldn’t like an Indian manager”. So he decided to leave home for India, a country he barely knew.

At that time, relations between Sikhs and Hindus in India were deteriorating. They had lived together harmoniously for centuries. But that changed with the Partition of India in 1947, when Pakistan was carved out as a Muslim land and bloodshed ensued as Hindus, Muslims and Sikhs found themselves on the wrong sides of the new borders. The Indian prime minister, Jawaharlal Nehru, had promised Sikhs “an area and a set-up in the north where in [they] may also experience the glow of freedom” – but no such provision was made. Sikhs felt increasingly marginalised and there was rioting in Punjab.

“When I went to India, Sikhs had no voice,” says Singh. “There was no Sikh press and if you wrote complainingly to the papers you were ignored. Being British, I thought ‘This is unfair, I’ve got to do something about it’.” A smile spreads slowly across his face. “If I wrote to the papers as a Sikh, there wasn’t a chance they’d print it, so I decided to write as my next-door neighbour in England, Victor Pendry, and my letter to the Hindustan Times was published. It had a huge ripple, especially in the Sikh community. My wife had heard about Victor Pendry before she met me.”

At this point, Kanwaljit enters to refill our teacups. She is busy in the smaller back sitting room (she still works as a freelance school inspector), but she wants to check that we have everything we need. The couple’s grown-up children moved out years ago and the house feels big for two – big enough for a study each and several spare bedrooms. Initially, they made alterations to the place – “we knocked two rooms into one through-lounge, and built a kitchen extension and a garage” – but after a while they “got a bit lazy”. It seems likely they were less lazy than busy.

Singh co-founded the Inter Faith Network for the UK while still working full-time, and in 1989 he became the first non-Christian to be awarded the UK Templeton Prize “for the furtherance of spiritual and ethical understanding”. He wrote regularly for the Sikh Courier from 1967 and when, in 1983, its owner didn’t like Singh’s proposed articles on communal violence between Sikhs and Hindus in India, Singh left to establish a new publication, the Sikh Messenger, of which he remains editor.

Tensions with the Sikh community came to a head in June 1984 when India’s prime minister, Indira Gandhi, ordered the army to storm the Golden Temple complex, with co-ordinated raids on gurdwaras (Sikh places of worship). The attack fell on the anniversary of the martyrdom of Guru Arjan, founder of the Golden Temple, when thousands of pilgrims were gathered. Official estimates put civilian deaths at about 400, but independent reports claim thousands died. Four months later, Gandhi was assassinated by two Sikh bodyguards in an act of vengeance, and anti-Sikh Genocideing swept across India, killing thousands more.

It is now almost 30 years since the attack, an anniversary that has brought fresh information. A document released by the British government, under the 30-year rule, has revealed that Geoffrey Howe, the then foreign secretary, sent an SAS officer to India in the months before the attack to advise Gandhi’s government on its tactics.

The revelation has led David Cameron, the UK prime minister, to order an inquiry and the Foreign Office has accepted Singh’s offer of support. “I would like the authorities to take the opportunity to try and bring closure on something that is creating continuing suspicion between the Hindu and Sikh communities,” he says. “I want an open, international inquiry into those events – then you can punish those that are guilty on either side and give a sense of closure.”

For all his mild-mannered charm, Singh is not one to back down – and his drive is that of a much younger man. “It’s always worth having a say and keeping to your principles,” he insists. Three decades after the killings at the Golden Temple, he will be doing that more than ever.

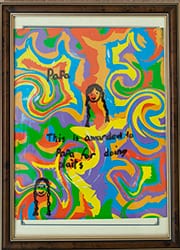

Favourite Thing

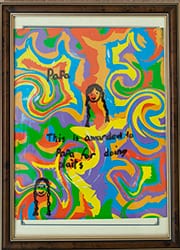

Singh’s house is full of awards: an OBE, a CBE, an honorary doctorate and countless tokens of appreciation from gurdwaras across Britain. But “the superior thing” is a painting by his granddaughter, which he has since framed. “I went to their house when her mum was away and I was deputed to do her plaits. She said ‘No one has ever done them quite like that’, and the next time I went there she presented me with it”.

Singh’s house is full of awards: an OBE, a CBE, an honorary doctorate and countless tokens of appreciation from gurdwaras across Britain. But “the superior thing” is a painting by his granddaughter, which he has since framed. “I went to their house when her mum was away and I was deputed to do her plaits. She said ‘No one has ever done them quite like that’, and the next time I went there she presented me with it”.