As a Sikh-African, I mourn and celebrate one of the greatest sons of Africa, Nelson Mandela.

Although most of the time I consider myself a Canadian, I have always felt a sense of pride in my African heritage, having been born in Kenya. Whenever Punjabis ask me what pind (village) I am from, I usually say “Obama’s pind!”

I was born in Kisumu on the shores of Lake Victoria, the source of the Nile River and the same place that President Obama’s family on his father’s side is from. I therefore feel a sense of affinity with both President Obama as well as Nelson Mandela because of my memories of Africa.

Although historical Africa has been romanticized in so many old movies, it also had a dark history of slavery and the colonial legacy of apartheid.

The word ‘apartheid’ literally means to ‘live apart’. A system of racial segregation enforced by law. Although it was the formal law of South Africa from 1948 to 1994, apartheid was practiced in South Africa and most of the colonial empires of European countries around the world for hundreds of years.

Outside of those colonies, you also see apartheid still in practice in countries like India with its medieval caste system and, to some extent, with the Blacks in the Southern United States and the aboriginal peoples in Canada. Although it may not be an official government policy in these and other countries, it is still a reality lived by hundreds of millions of people every day.

Nelson Mandela spent his entire life fighting apartheid.

I have some idea of what he was fighting. I lived it.

My family left Punjab for Kenya shortly after Partition and my grandfather, Sardar Sampuran Singh Gill, was the first non-white hired by the Kenyan Agriculture Department when he moved to Kisumu. He had broken through a colour barrier because he was a brilliant agriculture scientist and the British had recruited him to come to Kenya to apply his expertise there.

Even though I was born shortly after Kenya achieved its independence from Britain, the vestiges of apartheid were still alive and well. I was literally born into apartheid, the hospital in Kisumu where I was born was reserved only for European and Asian patients, no blacks allowed.

We lived on a sugar cane farm in the Rift Valley and the school that I attended had been reserved for whites only. I was one of the first non-white kids in my school, and that only happened because my father was very well respected among the local white farmers.

In post-independent Kenya, although Asians and Blacks lived and worked together, we lived in two separate worlds. Asians would socially interact with other Asians but never with Blacks. My grandmother would sternly warn my mother to keep the African servants out of the house as much as possible because, she said, they would bring diseases.

My young sister died of a tropical disease and my grandmother always blamed it on our African servants.

We never even envisaged visiting an African home or eating their food or shopping in their stores or visiting an African restaurant. When we made our safari to Nairobi, the capital of Kenya, we had no issues staying with even a Hindu family and eating their food.

The only African that ever visited our home was William Omamo and his family. Omamo was the Minister of Agriculture for Kenya at the time and had actually gotten his Master’s degree from Punjab Agriculture University (‘PAU’) in Ludhiana as a young man and had been a classmate and friend of my Dad, who had also received his Master’s from PAU.

At that time, PAU was — and still is — considered one of the premiere agriculture universities in the world and the preferred destination of agriculture students from many countries.

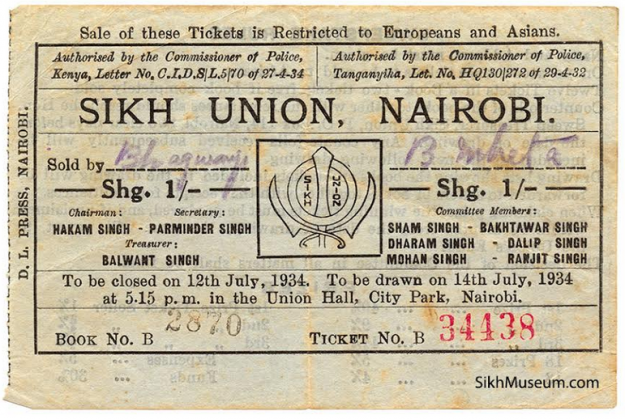

A few years ago during my research work for SikhMuseum.com, I came across a fascinating piece of Kenya’s apartheid history. It was a lottery ticket for a charity called “The Sikh Union, Nairobi.”

The Sikh Union would conduct lottery draws to raise money and the ticket was for a draw in July 1934. On the front of the ticket is a prominent Khanda logo for the Sikh Union and a listing of all the committee members and the fact that this lottery was authorized by the Police. On the back were the rules and regulations for the draw.

Incredibly, at the very top of the lottery ticket on the front is the following: ‘Sale of these Tickets is Restricted to Europeans and Asians’. On the back of the ticket, among the rules and regulations of the draw: ‘On no account are tickets to be sold to Africans.’ Both of these insertions were required by the apartheid laws of the country.

Thus, even this lottery ticket represents the harsh realities of apartheid in practice. Heaven forbid that an African should ever win the lottery; it would mean the end of the world!

Apartheid, that carefully constructed system of organized racism, was shattered when Nelson Mandela raised clenched fist as he was sent off to jail—where he remained for the next 27 years.

The other day I was reading a statement once made by Nelson Mandela and I was struck by its similarity to another statement that most of us know.

“It was only when all else had failed, when all channels of peaceful protest had been barred to us, that the decision was made to embark on violent forms of political struggle.” [Statement by Mandela at the opening of his defence in the Rivonia treason trial, on April 20, 1964.]

What does that remind you of?

“When an affair is past every other remedy, it is righteous then to put your hand on the sword” – Guru Gobind Singh, Zafarnama

In fact Mandela had been offered early release from jail by the South African government a number of times, but only if he would renounce the concept of an armed struggle, something he steadfastly refused to do. He never wavered from his passion and determination to see the cancer of apartheid and its bizarre ideas of racial superiority eradicated forever:

“The idea that any people can be inferior to another, to the point where those who consider themselves superior define and treat the rest as sub-human, denies the humanity even of those who elevate themselves to the status of gods.” [Mandela’s address to the UK’s Joint Houses of Parliament, July 11, 1996.]

Guru Nanak pursued that same mission throughout his life:

Recognize the Lord’s Light within all, and do not consider social class or status; there are no classes or castes in the world hereafter. [SGGS:349]

I like how Bhai Gurdas describes Guru Nanak:

In this Dark Age, he showed all gods to be just One.

The four feet of Dharma, the four castes were converted into one.

Equality of the king and beggar, he spread the custom of being humble.

Reversed is the game of the beloved; the egotist high heads bowed to the feet.

Baba Nanak rescued this Dark Age

[Bhai Gurdas, Vaar 1, pauri 23]

Comparing the commitment of Guru Nanak in the 15th century, and Mandela five centuries later, to ending the racism of social inequality, I am deeply disappointed in the beliefs of a 20th century icon often held in high regard, Mohandas K. Gandhi.

“I call myself a Sanatany Hindu who has deep faith in the caste system.” [Gandhi, Dharem Manthau, p. 6]

“I will oppose the separation of the Untouchables from the caste Hindus even at the cost of my life. The problems of the Untouchables have no relevance or importance before it.” [Gandhi, Round Table, London, 1932]

“According to me, the caste system is scientific. You cannot condemn it by argument. It controls the society socially and ethnically — I see no reason to end it. To end casteism is to finish the Hindu Religion. There is nothing against Varnastram. I have reason to believe that the caste system is an arithmetic principle. It has its own limitation and disadvantages. Even then there is nothing to be hated in this system.” [Gandhi, Harijan, l932 ]

Gandhi spent over 21 years living in South Africa and was exposed to apartheid in action first hand. Was he outraged at the social inequality of the system and its outright brutal racism?

Yes, he was, but not in the same way that Mandela was and Guru Nanak had been.

Instead of condemning the immorality of the apartheid system and its ethical bankruptcy, Gandhi was instead completely incensed that Asians were being grouped with Africans, who he considered animals, rather than with Europeans in terms of rights and privileges under the apartheid system.

Gandhi said on September 26, 1896 about the African people:

“Ours is one continued struggle sought to be inflicted upon us by the Europeans, who desire to degrade us to the level of the raw Kaffir (offensive term for Blacks, equivalent to the n-word), whose occupation is hunting and whose sole ambition is to collect a certain number of cattle to buy a wife, and then pass his life in indolence and nakedness.”

In the Indian Opinion of September 24, 1903, Gandhi said: ”

We believe as much in the purity of races as we think they (the Whites) do … by advocating the purity of all races.”

In the Indian Opinion of September 4, 1904, Gandhi wrote:

“Under my suggestion, the Town Council (of Johannesburg) must withdraw the Kaffirs from the location. About this mixing of the Kaffirs with the Indians I must confess I feel most strongly. I think it is very unfair to the Indian population, and it is an undue tax on even the proverbial patience of my countrymen.”

Enough about Gandhi, let’s talk about a real hero and role model, Mandela.

I think that Mandela will best be remembered not for what he did, but what he did not do.

Spending 27 years in jail he could have been full of hate and be waiting to seek nothing but revenge upon his release. He could have turned South Africa into a bloodbath of revenge. Instead he chose a path of reconciliation, where injustices and grievances were not forgotten, but revenge was not sought either, for the sake of peace.

He could have turned South Africa into a Rawanda or Zimbabwe, but he did not.

Perhaps Mandela had learned a lesson from the history of the horrors of mass ethnic cleansing as we witnessed in the Partition of Punjab and India in 1947 that left countless millions dead or homeless.

The path of reconciliation that Mandela took after his release from prison reminds me of the words of Guru Gobind Singh in Zafarnama, the letter that the Guru wrote to the Mughal Emperor Aurangzeb, a man that he should have hated after his four Sahibzadas had been killed:

Come to me that we may converse with each other,

And I may utter some kind words to thee. (60)

The Guru would go on to become close to Aurangzeb’s son, Bahadur Shah, who considered himself a disciple.

Sandeep Singh Brar is the Curator of SikhMuseum.com and the creator of the world’s first Sikh website, Sikhs.org.