CHANDIGARH, Punjab—The Tribune, the mainstream news outlet of India, has published an article written by the civil servant Gurbachan Jagat. In this article, Gurbachan Jagat has recalled an incident about the armed procession taken out by Sant Jarnail Singh Ji Khalsa Bhindranwale on May 29, 1981.

He has disclosed that he had convinced Sant Bhindranwale to take out this march peacefully but an objectionable march taken out by BJP MLA Harbans Lal Khanna on May 28, 1981 reverted the situation.

“On May 28, when I was going back to office after lunch, I heard a lot of sloganeering. I was informed that some boys belonging to a particular community and led by BJP MLA late Harbans Lal Khanna had taken out a procession in vehicles and most of them were smoking cigarettes and showing them off. Objectionable slogans were raised and on the way they tossed up the turbans of a couple of Sikhs. The atmosphere in the city and especially around Darbar Sahib was surcharged with tension. The procession for the 29th was revived, and this time Bhindranwale would lead it. I was asked to get in touch with him again but I refused, knowing that in light of the obviously provocative, mischievous procession of the 28th, there would be an immediate response from Bhindranwale in the form of reviving his armed procession,” he writes.

Read below the full excerpt of the article written by Gurbachan Jagat, the then SSP Amritsar:

“The last few years have been troublesome for sensitive and perceptive people, and some of us have voiced our apprehensions to each other from time to time. The atmosphere building up in the country is one of discord, disunity, hatred of the ‘other’, no tolerance for dissent and all dissent is sedition and anti-national. Speeches and writings of senior political, religious and cultural leaders are divisive in nature. Where will all this lead? We have created belligerent cult leaders in the past also, to which political leaders of all hues contributed. In the end, the puppets became the puppeteers for some time before the chaos and violence they unleashed could be brought under control. It is time to pause and take a hard look at what we are creating, the forces and fury we are unleashing — time is of the essence.

I want to narrate a small link in the chain of events that wreaked havoc in Punjab for more than two decades. Small innocuous beginnings organised by the people of the type mentioned above led to the drama of death and violence. One such incident, orchestrated from behind the scenes, while I was posted as the Amritsar SSP occurred in 1981 in the form of an anti-tobacco march.

Militancy had started picking up under the leadership of the Damdami Taksal based at Chowk Mehta near Baba Bakala. The head of the Taksal was Jarnail Singh Bhindranwale, a relatively young and unknown person at the time of his taking over after the death of Sant Kartar Singh in an accident. In the aftermath of the Baisakhi clash of April 13, 1978, the Taksal remained busy in agitating against the Nirankaris. However, Bhindranwale was consumed with the humiliation he had received in the Baisakhi clash and was always looking out for causes he could take up to challenge the state. By 1981, he had acquired a strong following. The role played by various parties in helping in sustaining and strengthening this militancy and allowing its followers to get armed was only to further their own political agendas.

The incident I want to narrate began with the floating of the idea of having Amritsar declared as a holy city. Further, smoking of tobacco was sought to be banned in the city. Bhindranwale was staying in Guru Ram Das Ji Serai, which was the doing of SGPC president Gurcharan Singh Tohra. There was a Congress government in the state headed by Darbara Singh.

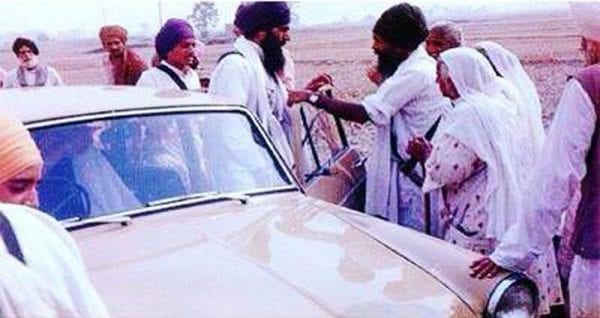

Bhindranwale announced that he would take out an armed procession from Sri Darbar Sahib to the Baradari on May 29, 1981, and himself lead it. This announcement led to a lot of concern and various efforts were made to forestall the march. I was asked, rather directed, to meet Bhindranwale to persuade him to give up the march. An appointment was fixed at his place and this was done through Amrik Singh (son of Sant Kartar Singh), who was a far more reasonable person. I was to go alone without any security.

He as usual was sitting on his bed and there was a chair for me, which was a good sign because he normally did not offer one to visitors. After the usual pleasantries, I came to the point and requested him to withdraw his call for a procession and that the government would consider the issue of placing a ban on smoking in the city. His immediate response was to reject the request. He said he had given his word to the ‘sangat’. For the next hour or so, we went back and forth and I ultimately told him that I was not going to leave the room till he had agreed to my request. He then went out and conferred with Amrik Singh and told me that an unarmed march would take place and would go only up to the Kotwali, a short distance from Darbar Sahib. He also agreed not to lead it personally. He wanted an officer to receive a memorandum at the Kotwali, after which they would disperse. I thanked him and informed the government (perhaps a bit too soon).

However, events were to take a different turn the next day. On May 28, when I was going back to office after lunch, I heard a lot of sloganeering. I was informed that some boys belonging to a particular community and led by BJP MLA late Harbans Lal Khanna had taken out a procession in vehicles and most of them were smoking cigarettes and showing them off. Objectionable slogans were raised and on the way they tossed up the turbans of a couple of Sikhs. The atmosphere in the city and especially around Darbar Sahib was surcharged with tension. The procession for the 29th was revived, and this time Bhindranwale would lead it. I was asked to get in touch with him again but I refused, knowing that in light of the obviously provocative, mischievous procession of the 28th, there would be an immediate response from Bhindranwale in the form of reviving his armed procession.

We had a long meeting at the Kotwali and it was decided that officers would be deployed tactically along the route and with the procession. Experienced officers would bring up the rear as it could be a major source of trouble. Another key decision taken was to remain deployed during the dispersal of the crowd, which would be in the form of small groups going in different directions.

The procession began and there were thousands of persons with all types of arms. The bazaars were closed and not a soul was to be seen along the route. I was at the head alongside the Taksal leadership and we were virtually jogging, perspiring profusely and perpetually thirsty. We were kept hydrated by the volunteers of the Taksal, who, in the true Sikh spirit, gave water to the protesters as well as the policemen. Along the way, the wireless chaps kept on reporting clashes and deaths. I told myself to get the procession to reach its destination and then take stock. We reached the Baradari, a few kilometres from Darbar Sahib, in record time, where after short speeches the dispersal started. I stationed myself at the Kotwali, where we had kept about 15 mobile groups. During dispersal, these came in handy and I kept on dispatching them to trouble spots. Finally, I was left alone with my vehicle. At this stage, Amrik Singh and Avinashi Singh (PA to Tohra) came to me and said they had kept their promise that no violence would take place. Just then, information came that Bibi Amarjit Kaur, a firebrand, was heading towards Dr Baldev Prakash’s clinic in an interior location. I had nobody to send and I requested Amrik Singh and Avinashi Singh to go in their own car and bring her back. Dr Prakash was a senior BJP leader and a very decent human being. Fortunately, they reached in time and brought her back to the Kotwali. After that, I waited for the officers to come back and report. It was heartening to hear that not a single death or clash had taken place and all the reports to the contrary were ‘fake news’. Although there had been grave apprehensions of large-scale violence, the police managed to ensure that no such thing happened in spite of being outnumbered and ill-equipped.

In the next couple of days, I went over the whole chain of events and came to the conclusion that the pro-smoking procession led to all our immediate problems, which were to increase later on. Within a few months, I was offered a deputation to the CBI, which I accepted. When I reached Delhi, I was met at the railway station by some of my batchmates, who informed me of major trouble at Chowk Mehta that day and of people having died in police firing. Mischief was really afoot, but for the time being, I was out of it.

Today, once again, divisive forces are hard at work creating a similar witches’ brew and we are standing at the crossroads of history, not knowing which path this country will follow. To the men in uniform, I can only say it is under your watch now and in these difficult times, be true to your oath and follow the law of the land.”