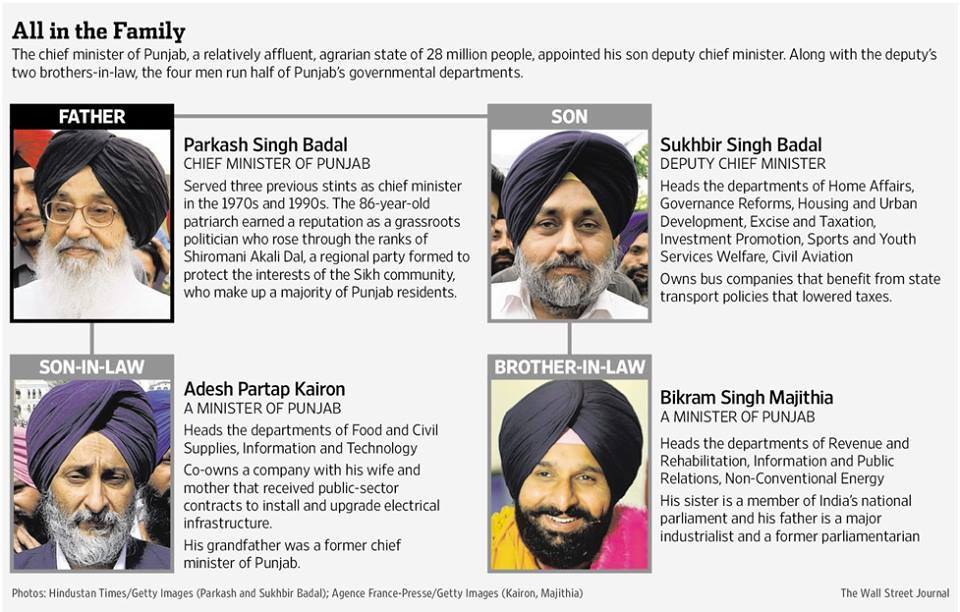

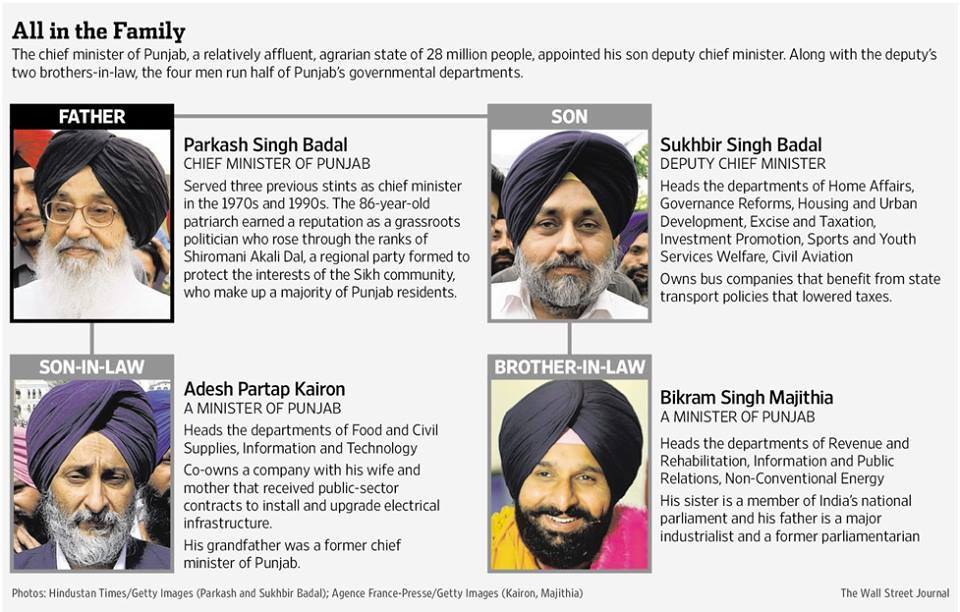

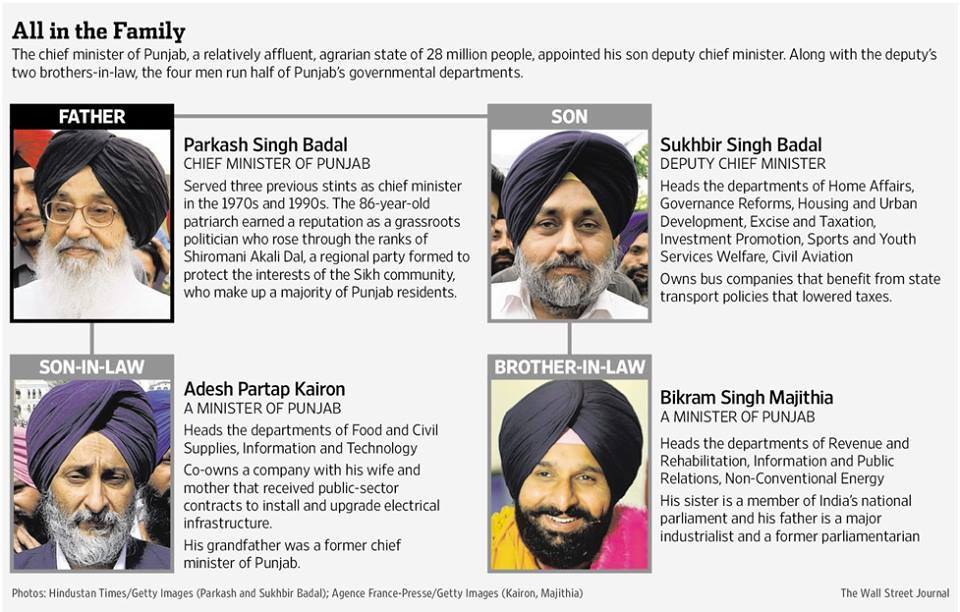

CHANDIGARH, Punjab—Chief Minister Parkash Badal runs the northern Indian state of Punjab from his office in the secretariat building. His son, a wealthy businessman, works next door as deputy chief minister.

A few floors away, the deputy’s two brothers-in-law run key ministerial offices. Together, the four men sit atop half of Punjab’s governmental departments, including home affairs, justice, taxation, and food supply.

Politics in Punjab, an agrarian state of 28 million, is largely a family-run operation, which isn’t uncommon in a country governed for decades by the Indian National Congress, the party of the Nehru-Gandhi clan. But frustration with family politics has surfaced in India’s national elections, which end with the announcement of results Friday. Political analysts and voters say this frustration is an important reason why Prime-Minister candidate Narendra Modi, a critic of dynastic politics who said he gave up family life for public service, is the front-runner. He was leading in exit polls Monday. The father, grandmother and great-grandfather of his opponent, Rahul Gandhi, all served terms as Prime Minister in India’s postcolonial era.

While the U.S. has its own dynastic family names, Kennedy, Bush, and Clinton, none match the depth of India’s family ties. A British historian in a 2011 study found that two-thirds of India’s national parliamentarians under 40 were related to other politicians. And voters here have grown increasingly suspicious that such family networks use policy-making and executive authority to enrich themselves and their protégés.

In Punjab, a Wall Street Journal review of financial and government documents, as well as interviews, found Mr. Badal’s relatives have benefited financially during his administration, with government decisions on transportation and electric power favorable to family enterprises. Badal family connections in regional TV news broadcasting, meanwhile, have had the effect of squelching voices critical of the arrangement, according to political opponents.

A spokesman for Mr. Badal, Harcharan Bains, said, “There is no unwritten convention or written law” in India that people in public life can’t have business interests. The Badals say their business deals are kept at arm’s length, and deny any abuse of power. Voters support them, they say, because they improve the lives of constituents, expanding infrastructure and development, for example. “This family system runs because of credibility,” said deputy chief minister Sukhbir Badal, age 51. “Why do people want to buy a Mercedes car? Or a BMW car? Because they know the credibility of that car. You come out with a new car that nobody knows, nobody will buy it.”

Mr. Badal served two brief stints as chief minister in the 1970s, and then a five-year term from 1997 to 2002, earning a reputation as an effective grass-roots politician. During visits, he would sit under a tree and ask villagers their problems, residents recalled, then press officials to respond.

Badal family fortunes turned up in the months after Mr. Badal’s re-election to chief minister in 2007. The state cabinet, which he heads, overhauled Punjab’s transportation policy, making it less expensive to operate luxury buses. Air-conditioned buses had always been taxed at higher rates than ordinary buses. But a new transportation policy slashed levies on air-conditioned buses and set taxes, charged per kilometer, for a new category of luxury buses that was lower than the tax paid by ordinary buses.

A bus company owned by Sukhbir Badal, the deputy chief minister, saw profits grow to more than ₹105 million, or $1.7 million, in 2013 from ₹2.5 million, or $41,000, in 2007, according to the company’s financial statements. He said his company, Dabwali Transport, grew by acquiring other bus companies, and acknowledged the lower tax rate helped his business.The transport minister at the time, Master Mohan Lal, told the Journal the change was made to improve services. Sukhbir Badal, who wasn’t in office when the change was made, said it was designed “so that even the common man can travel in luxury without paying high rates.”

The number of air-conditioned buses has since grown, offering fares that are only slightly higher than ordinary buses, according to transport department officials. Fares of luxury buses are roughly twice the cost of ordinary buses.

Since the tax cut, the family’s business has grown to dominate luxury-bus travel in Punjab, particularly in Bathinda, which has more than a million residents. More than half the permits for luxury and air-conditioned buses granted to private operators by the regional transport authority statewide, and more than 90% of those in Bathinda, belong to two transportation companies owned by the family, according to government documents, and a third company, Taj Travels, which is owned by a man who is a director in hotel and real-estate companies also controlled by the family.

Sukhbir Badal’s declared assets have grown to more than ₹1 billion, or about $16 million, from ₹130 million, about $2.1 million, in 2004, according to documents filed to India’s election commission. In 2009, his wife won a seat in the national Parliament.

Indian government guidelines require ministers to fully disclose business interests and step away from management after taking office. The guidelines also say ministers must divest themselves of all interests in businesses that supply goods or services to the government or rely on official permits or licenses. In states, chief ministers are charged with making sure the guidelines are met but, according to an official in the home ministry, the guidelines are rarely followed.

The elder Mr. Badal, in a written response to the Journal, said he doesn’t take an active role in any family related business. If family businesses have grown, he wrote, “it is only a part of the success story of all Punjabis over the past 60 years.” After another re-election in 2012, Mr. Badal’s term goes to 2017.

In 2008, two months after Mr. Badal’s 80th birthday, party delegates elected Sukhbir Badal as party president to succeed his father. Mr. Badal said his son was promoted for helping return the party to power.

A year later, Mr. Badal appointed his son as deputy chief minister. Sukhbir Badal, who has a master’s degree in management from California State University, Los Angeles, had previously served in India’s national Parliament. He was later voted into the state legislative assembly, a requirement for deputy chief minister.

Mr. Badal said “it was natural” to give his son the job because of support from voters and the party. Sukhbir Badal said his father “wanted me to take over, to share his responsibilities.” He also didn’t want to abandon hundreds of thousands of party workers who feel more secure under the Badals’ leadership, he said.

Mr. Badal’s daughter, Parneet Kaur, has also prospered during her father’s time as chief minister.

From 2009 to 2013, state-owned power enterprises awarded contracts valued at ₹3.9 billion, about $64 million, to consortia that included a company majority-owned by Ms. Kaur, her husband and her mother-in-law, documents show. The contracts were first reported by the Tribune, a regional newspaper, and viewed by the Journal, which verified them with the Punjab State Power Corp.

Mr. Badal, Ms. Kaur’s father, chairs the state’s power department, and Ms. Kaur’s husband, Adesh Partap Kairon, works as Mr. Badal’s minister for food supply and information technology.

Sukhbir Badal sought to revitalize Punjab’s power sector through policy directives that resulted in bids for a government contract to install and upgrade electrical infrastructure. A ₹2.3 billion deal, or about $38 million, was awarded a year ago to a team of three companies that included Shivalik Telecom Ltd., which manufactures and installs electrical infrastructure, and is owned by Ms. Kaur and her relatives.

Ms. Kaur’s declared assets grew to $2.7 million in 2012 from less than $800,000 in 2007. Ms. Kaur and her husband didn’t respond to requests to comment.

“We have never favored any company,” said K.D. Chaudhri, chairman of the Punjab State Power Corp. The bids were judged on well-defined criteria, including technical expertise, and the contract awarded to the lowest bidder, he said. He didn’t identify the companies in contention.

Mr. Bains, spokesman for Mr. Badal, the chief minister, said, “No law, or even established rules of propriety have been violated, nor has there been undue favor,” in contracts awarded to Shivalik Telecom.

The Badals have also expanded their media interests. In 2006, they started a local TV company with a 24-hour news channel, PTC News, which has become one of the most popular in the state, according to residents.

Billboard images across the state show chief minister Parkash Badal; his son, Sukhbir Badal; and Sukhbir’s brother-in-law, Bikram Singh Majithia. Official cards that entitle Punjabis to subsidized grain bear the photographs of the chief minister and his son-in-law, Adesh Partap Kairon, who is the minister of food supply. An oval cutout of Mr. Badal’s face was added to the baskets of thousands of free bicycles given to female students. At a recent rally in Amritsar, Gurudev Singh, 35 years old, said he was voting for the coalition run by the Badal family’s party for a national Parliament seat in the current election. “I come from a family of shopkeepers,” he said. “Their career is politics. It’s a one-family rule, yes, but that’s how politics work in India.”