NEW YORK, NY—When Prabhjot Singh, a Sikh professor at Columbia University in the US, was brutally injured in a hate crime a month ago, his response bewildered many. Instead of anger at being wrongly targeted as a terrorist, Prabhjot said he simply wanted to express gratitude for being alive and for the fact that his family was unharmed. He also said he would want to educate his attackers and “invite them where we worship”.

In August last year, six people were gunned down in a gurdwara in Wisconsin. The attack on Prabhjot — whose turbaned and bearded appearance prompted the attacker to call him Osama — was just one in a series of assaults on Sikhs abroad, establishing that such community-specific crimes haven’t been isolated. A timeline of attacks against Sikhs after 9/11 shows that there have been over 20 incidents where Sikhs were assaulted, killed and Gurdwaras vandalised. Anecdotal figures peg the worldwide Sikh population at 23 million; of these, a significant proportion reside in the US, UK and Canada.

So, why are Sikhs so often singled out?

Despite being the fifth-largest religion in the world, many communities remain unaware of the basic tenets of the faith — what the turban or dastaar represents, for instance.

“The Sikh image can look ferocious. The turban and flowing beard can intimidate people…the biggest misrepresentation to dispel is that those who maintain their identity are not terrorists,” says Jay Singh Sohal, journalist, filmmaker and author of Turbanology: Guide to Sikh Identity.

As debate continues in many parts of the world over the rights of Sikhs to wear the turban — and other symbols such as the kirpan — efforts to increase awareness about the religion are taking place across countries, by individuals as well as groups.

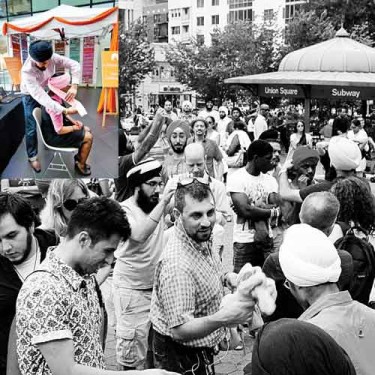

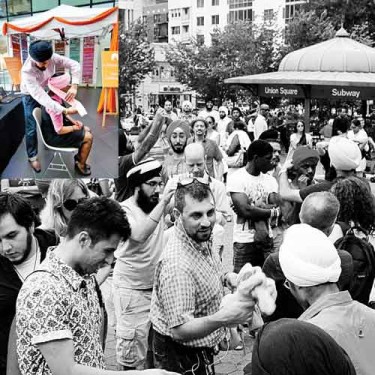

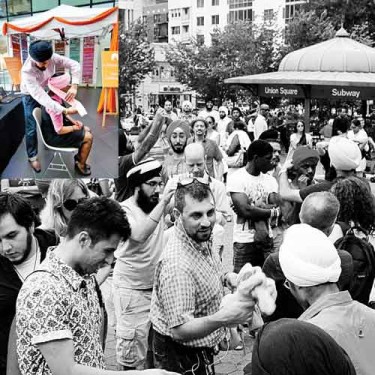

Just a few days after the attack on Prabhjot, The Surat Initiative, a US-based NGO focusing on educational advocacy and key issues pertaining to the Sikh community, organised a Turban Day in New York. As part of the initiative, volunteers tied over 700 turbans on their fellow Americans in an effort to share their faith and educate other communities. “The response to Turban Day has been incredible. We have been conducting it in cities all over the US. People of all backgrounds have loved it and appreciated the opportunity to learn about Sikhism,” says Simran Jeet Singh, director of education, The Surat Initiative.

While he was never subjected to racism, Sohal, who was born and brought up in UK’s Birmingham city, at the forefront of the turban rights campaign during the ‘80s, first came across misconceptions about identity during his stint as a regional TV reporter. “It was while making a documentary titled Turbanology: After 7/7 that I was able to look at how the advent of jihadism had changed things for Sikhs, who are often mistaken for Islamists.” The documentary gave way to the Turbanology project, an arts exhibition that toured the UK. The exhibition catalogues the different types of turbans that Sikhs wear and explains the concepts it represents (pride, honour, respect) through art, to connect with a larger audience.

Gurbachan (Gorby) Singh Jandu, another Sikh living in the UK, found his own way to contribute to global awareness about his religion. Jandu, an anthropological researcher as a Fellow of the Royal Anthropological Institute (RAI), will try to display a collection of turbans he picked up from various countries at the Horniman Museum in London in the summer of 2014.

Jandu started wearing a turban when he was 13 and continued till he was 17, when he migrated to London from Kenya. “I decided at the age of 17 that I could no longer uphold the values that the dastaar in my mind demanded. I had elder Sikh males such as my dad, cousins and uncles who had stories of experiences with the pagh so I was able to consider what being a practising Sikh entailed,” he says, explaining why he does not wear a turban now. Jandu travelled to Kenya, the US, Scandinavia and India to interact with turban-wearing communities. “The one connective aspect I discovered was the willingness of most participants, religious leaders, elders, children and even non-Sikhs, to talk about the pagh in both its secular meaning as much as its religious one,” he says.

He cites the example of Kenya’s Makindu gurdwara where the black staff wear the turban even when they’re not working, not because they have converted but out of respect — heads should be covered in all gurdwaras. This has been the norm for the last 50 years.

Jandu’s reason for choosing the turban as a research subject was simple. “All around the world, Sikhs are parenthetically associated to turbans, but what about the majority of them who are not?

My interest in Sikhs is based on the borderlands between religion and culture; I felt that there was a research gap where secular heritage, tradition and culture interacts with the beliefs and practices of everyday Sikhs.”

As a part of his research, Jandu also observed that the pagh had undergone a change in fabric, prints and styles.

Jandu believes that ethnically-motivated crimes in the UK are less of a populist issue than, for instance, in the US. “However, crimes motivated by differences have not been eradicated in Britain and many still suffer needlessly through ignorance, something I dearly hope the Horniman Sikh Turban Project will help change.”

Initiatives like these will hopefully go a long way in fostering tolerance amongst different nationalities and bring down targeted hate crimes.