Part 1 Continued

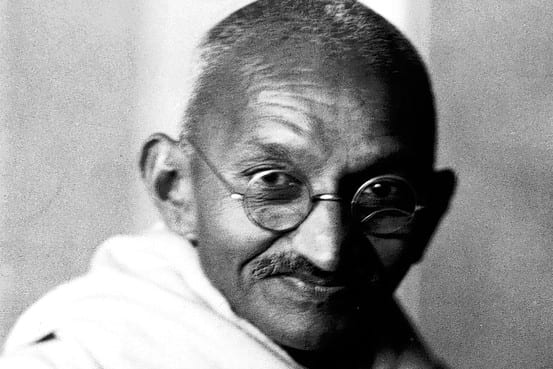

Even before Gandhi came to India in 1915, the Sikhs had been peacefully protesting for the right to run their Gurdwaras (after the Sikh kingdom had been annexed, the Gurdwaras had been turned over by the British to Brahmin Hindus to run). Gandhi was very critical of the ‘Sikh way’ of civil disobedience. He said:

“The Akalis (Sikh Warriors) wear a black turban and a black band on one shoulder and also carry a big staff with a small axe on the top. Fifty or a hundred of such groups go and take possession of a gurdwara; they suffer violence themselves but do not use any. Nevertheless, a crowd of fifty or more men approaching a place in the way described is certainly a show of force and naturally the keeper of the Gurdwara would be intimidated by it.” (Collected Works of Mahatma Gandhi, Vol. 19 pg. 401).

This is where I do not understand Gandhi’s teachings. On the one hand Gandhi did not believe non-violent resistance should be “passive,” but rather that it should be, in essence, a “force”. On the other hand, he criticized Sikhs for practicing non-violent civil disobedience in seeking control of their Gurdwaras. Their methods were even praised by British leaders. Reverend C. F. Andrews wrote: “The vow (of non-violence) they (the Sikhs) had made to God was kept to the letter. I saw no act, no look, of defiance.”

As far as the spirit of the suffering they endured, the Reverend said “It was very rarely that I witnessed any Akali Sikh, who went forward to suffer, flinch from a blow when it was struck. The blows were received one by one without resistance and without a sign of fear.”

Still, Gandhi could not reconcile this manner of civil disobedience, for he decided that the Sikhs participating in it harbored “hatred in their hearts” and thus never gave his blessings to such forms of agitation. Gandhi could not understand why Sikhs would peacefully protest while wearing arms. To him, this constituted cowardice, that one carries arms while walking in peace.

I completely disagree. Gandhi failed to realize the differences between non-violence of the weak, and non-violence of the strong. The importance of carrying arms was to show that they were indeed brave enough and capable of using them, but that they were instead consciously choosing not to. It is a discipline that only a few select can conquer. A coward who is weak and scared will never wear arms and walk in peaceful protest because, as soon as the first signs of oppression arise, he will be scared and use his weapons in haste. Similarly, the weak and the scared will never have the capacity to make non-violence their way of life. To them it will only be something useful when they are helplessly bound in shackles.

To be able to wear arms and to not retaliate or show the slightest bit of anger or attempt self-defense against someone who is attacking you is the highest form of non-violent protest. It implies a complete resignation to peaceful ways and an absolute belief in the power of non-violent protest despite the ability of the protestor to respond violently. It is one thing to walk in peaceful protest that is born out of a feeling of helplessness and quite another to walk peacefully, inviting oppression and suffering upon himself despite being fully armed, while totally being able to fight back. The first constitutes cowardice, the second a force.

I can’t help but think that the sort of non-violence practiced by Gandhi’s followers in India was that of the weak, that of the helpless. I believe that most did not truly understand the principles of non-violence in the manner in which Gandhi preached it. Rather they just thought they would be unable to win independence through other means. I come to this conclusion because of the history of Indians both before and after Gandhi.

An obvious fact is that Indians as a race have been oppressed for the last several hundred years by the Moguls (and later on by the British). Many of them never uttered a word of protest against the atrocities that were committed against their kith and kin, atrocities which were much worse than those perpetrated by the British. Even fewer actually took up actions against the Moguls (the major exception of course being the Marathas in the south).

It was quite common for invaders such as Abdali and Nadir Shah to invade India, take Indian jewelry and Indian women and head back to Afghanistan. Yet there were very few strong voices that opposed this. This was because of fear. This fear is what stopped them from participating in any course of action besides submitting to their oppressors. It seems like over time most Indians have developed a “learned helplessness”. Following Gandhi’s ideas arose from this feeling of helplessness. Indians followed Gandhi’s beliefs not because they thought non-violence was a superior weapon in dealing with social problems, as Gandhi had preached, but rather because they felt they had no other alternative. This in itself defeats the whole purpose of non-violence.

It was quite common for Indians to one day be peacefully protesting and the next day to form lynch mobs. The only conclusion I can come to in order to reconcile these two thoughts is that they had no idea what the real essence of non-violent agitation was. The simple fact that after Gandhi his philosophy of non-violence has been completely abandoned by the people of India at large seems to point toward this conclusion.

To me, Gandhi came across as being an uncompromising extremist. A non-violent extremist, but an extremist nevertheless. His letters to the British people during World War Two encouraging them to “allow yourself, man, woman, and child, to be slaughtered” by “peacefully surrendering” to the Nazis in order to further his fanatic ideas of non-violence is a perfect example (CW Vol. 72 pg 229 231, CW Vol. 72 pg. 177). When pressed even further, he went to the extent of calling Guru Gobind Singh, the Maratha Shivaji and George Washington “misguided patriots” for taking up arms in defense of their people (CW Vol. 26 pg. 486-492).

Had Gandhi lived under the likes of Aurangzeb, in almost all likelihood he would have been arrested and hanged for even showing the slightest bit of defiance to the Mogul Empire. His non-violent ways worked because the British were not total tyrants, rather just concerned with exploiting Indians for their own economic gain. The aim of the British was not to annihilate them, as Aurangzeb and Hitler had attempted to do to their subjects. Thus the situation was ideal for the implementation of non-violent agitation.

According to Gandhi, only “evil and violence” came about from those who use violence. He seems to totally disregard the idea of a “noble cause”, basing his ideas of whether a movement was right or wrong on his narrow view of whether or not non-violence was being used. No doubt history has shown that those who used violence for the sake of unworthy causes ultimately did perpetuate violence and evil upon themselves. But, at the same time, those who used violence because of noble causes (as in defense of their people), the rule did not apply.

There is a certain undeniable beauty in watching or reading about others who are fighting for noble and legitimate causes. Perhaps one of the best examples I can bring up is reading about the American Revolution. There is certain magnificence, certain holiness, about those people fighting for their rights. The fact that they used arms to achieve their freedom did not discount the righteousness of what they did.

To be continued…