THE BLACK PRINCE is a 2017 international film which tells the story of the last king of the Sikh Empire and the Punjab, Maharajah Duleep Singh and Queen Victoria. We thought it would be nice to share an article on ‘Maharaja Duleep Singh and British Values’.

Maharaja Duleep Singh and British Values

Values are principles or standards of behaviour. It is ideal if personal and social life is organised around a constructive consistent and compelling system of values.

There is a consensus among political and religious leaders that fairness, equality, freedom of speech and tolerance are the most important British values.

They are grounded in Christianity. Practically all the politicians and priests tell the public that terrorists and proponents of extremist ideologies should be taught British Values.

In this article, we shall be exploring if these values were adhered to or put aside from 1840 onwards in the Punjab by officials of the East India Company.

So first of all, let us try to understand the functions and the parameters of the East India Company.

East India Company (1600-1858) was chartered by Queen Elizabeth-I and given a monopoly of trade between England and the Far East. In the 18th century, the company became in effect the ruler of a large part of India and a dual control by the company and a committee responsible to Parliament in London was introduced by Pitt India Act 1784.

Let us now turn to the Punjab in the 1840s. Maharaja Ranjit Singh, the Lion of Punjab died in 1839. After his death came the inevitable fall, for there was no powerful leader to take over his rule as he had not trained and positioned anyone to succeed him.

Prince Duleep Singh, the youngest of the seven sons of Maharaja Ranjit Singh was born in the Lahore Palace in 1838. He ascended the throne of Lahore after bloody struggles for succession at the tender age of 5 years and his mother Maharani Jind Kaur was to be his Regent.

The East India Company had refrained from having a direct clash with Maharaja Ranjit Singh, but after his demise, the first Anglo-Sikh war broke out in 1845. The British emerged victorious, but did not annex the state on practical grounds. At the same time, the Company did not want the Punjab to remain independent. So by the Treaty of Bharowal, of 1846, the British Resident had become the virtual ruler of the Punjab.

The Multan incident took place in 1848 just after the arrival of Lord Dalhousie as the Governor General of India. No action was taken for five months and it could have been easily put down. Dalhousie papers clearly indicate that immediate advance on Multan was neither perilous nor impracticable.

Instead, the British made military preparations for a full scale war in the Punjab and its final annexation were set afoot. The Governor General began to call the Multan revolt a national rising of the Sikhs. The “die is cast” declared Lord Dalhousie. On March 1849, the kingdom of the Punjab was annexed to the British Crown.

In other words, the East India Company held the Lahore Darbar responsible for the Second Anglo-Sikh war, when in fact the power behind the throne was the Resident according to the Treaty of Bharowal.

It must be stated here that some of the distinguished British civil servants like Sir Henry Lawrence and Fredrick Currie vehemently opposed the annexation and described it as ‘unwise and impolitic.’ This infuriated Dalhousie who removed Lawrence from the residence of Punjab and dispatched him to Rajputana. (Maharaja Duleep Singh – The Last Sovereign Ruler of Punjab, p. 31)

Duleep Singh was immediately removed from his mother, Maharani Jind Kaur – commonly known as Maharani Jinda, when he was only 11-12 years. Hence an eleven year old child was separated from his mother. Duleep Singh was taken to Fatehgarh, a small village in Farrukhabad district. His mother Maharani Jind Kaur was first held in the fort of Sheikhupura (now in Pakistan), and then sent to Benares.

Most psychologists agree that a mother or a significant other have a very significant part to play in the formative years of a child. A significant other should be one whom the child loves and the family trusts. A mother or father infuses in a child the confidence and courage to understand and face the dynamics of life.

What did the new rulers of Punjab do? They flagrantly violated the basic human decencies by depriving the young Duleep Singh of the loving and warm embrace of his mother.

Tolerance of Religions

The consensus in this country is that Tolerance is one of the top British values. Tolerance is respect, acceptance and appreciation of the rich diversity of world’s cultures, belief systems or religions. The young Duleep Singh knew only Christian friends, Christian tutors and Christian ethos. He had no access to a Gurdwara or a Granthi.

After weaning him away from the faith of his ancestors, Dalhousie claimed that, “with the conversion, the political influence of the Maharaja had been destroyed forever.” (Lord Dalhousie to Dr. Login, 23 July 1851)

In his letter to Dr. Login, the Governor General of India was forthright in stating his aim, “I do not want to countenance any relations henceforth between the Maharaja and the Sikhs, either by alliance with a Sikh family or sympathy with Sikh feeling.” (13 April 1850, quoted in Maharaja Duleep Singh, edit. Prtihipal Singh Kapur, p. 83)

In March 1853, Duleep Singh was quietly baptised a Christian at a private ceremony at Fatehgarh. In April 1854, the Maharaja and his party sailed for England.

Koh-i-Noor Dimond and Fairness

To be fair, requires us to treat others equally, or – ‘Not do to others what would cause pain if done to you.’

Below is an extract from an article by William Dairyample-co-author of Koh-i-Noor –The History of the Word’s Most Infamous Diamond in the Daily Telegraph. Also quoted in Sir John and Duleep Singh by Lady Login, p. 342

In July 1854, Queen Victoria found herself faced with a conundrum. The Koh-i-Noor diamond had been presented to her four years earlier by the Governor-General of India, Lord Dalhousie, who had seized it from Sikh Maharaja Duleep Singh at the British conquest of the Punjab. Now, however, Duleep Singh was her guest at Osborne.

Characteristically, the queen decided to grab the nettle: “Maharaja,” she said one afternoon, “I have something to show you.” Duleep Singh moved forward towards her not knowing what to expect. The queen took the jewel from its box and dropped it into his hand.

The Maharaja held up the diamond to the sunlight. “For all his air of polite interest and curiosity,” wrote one observer, “there was a passion of repressed emotion in his face…evident, I think, to her Majesty, who watched him with sympathy not unmixed with anxiety.”

The awkwardness in the room grew. “At last, as if summoning his resolution after a profound strength, he raised his eyes from the jewel. I was prepared almost for anything,” recalled his former guardian, Lena Login, “even to seeing him in a sudden fit of madness, fling the precious talisman out of the window. My own and the other spectators’ nerves were equally on edge as he moved to where Her Majesty was standing.”

Bowing before her, he gently put the gem in Queen Victoria’s hand…The tale ultimately had much less happy end. The loss of the Koh-i-Noor continued to play on Duleep Singh’s mind and he ended up referring to the Queen as Mrs. Fagin – a receiver of stolen goods…

An Ethical Question which William Dalrymple answers without mincing his words:

“The story of the Koh-i-Noor is in many ways a touchstone for attitudes towards colonialism, posing the question: what is the proper response to imperial loot?

Do we shrug it off as part of the tough – and-tumble of history, or do we right the wrongs of the past? Few today would disagree that Jewish art stolen from its owners during the Holocaust of the 1940s should be returned, but we tend to treat as a very different case Indian treasures looted in the 1840s.”

Let us get back to Maharaja Duleep Singh again.

In 1861 Duleep Singh visited India, but was not permitted to go to the Punjab. Quite cautiously, he was restricted to Calcutta where his mother Maharani Jind Kaur, then living in Kathmandu in exile met him. Duleep Singh took her to England.

The arrival of Jind Kaur in England was described as “misfortune” for the Raj (Lady Login, pp 464-465) because the Maharaja was getting under his mother’s influence. In other words, the East India Company and the British government were interested only in maintaining their Raj in India and not happy when long parted mother and son met again.

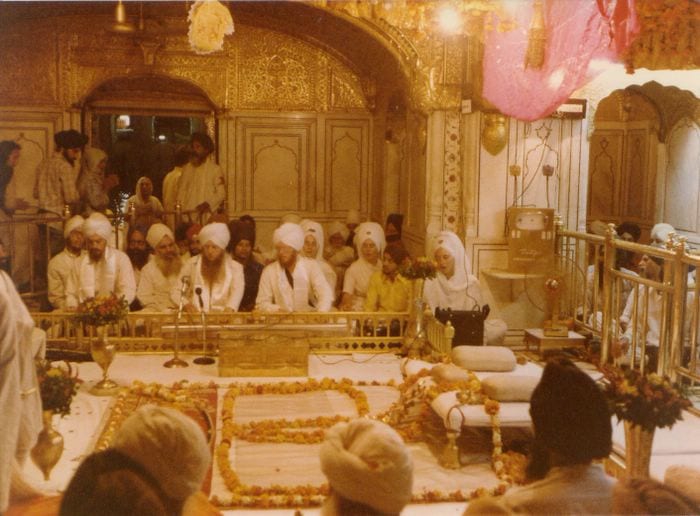

The presence of Maharani Jind Kaur in England stirred the dormant patriotic urges of the Maharaja. Before her death in 1863, Maharani Jind Kaur had enlightened her son about his glorious royal heritage, and the insidious intrigues and conspiracies of the East India Company who had usurped the Sikh state. This rekindled him the urge to take the British government head on. He later on took Amrit and was baptised a Sikh.

To sum up, young Duleep Singh was deprived of his mother’s love and protection, coerced into signing some treaties that were used against him, deposed as a Maharaja, manipulated and westernised by his Christian advisers obeying the orders of people higher up and weaned away from his religious and cultural roots.

One wonders why the Empire builders did not remember their values when they had the power.

Sohan Singh

England

Sohan Singh, a Sikh author, is also one of AWAT Editors

Click here to watch “THE BLACK PRINCE – Official Trailer 2017” if you haven’t watched the movie yet.