April 25 marked the centenary of the landing of the Australian and New Zealand (Anzac) troops in Gallipoli, for their World War-1 military campaign that went on for eight months and claimed at least 1.25 lakh lives. Many regard April 25, 1915, as the day Australia truly forged its national identity, even though it was declared a nation January 1, 1901.

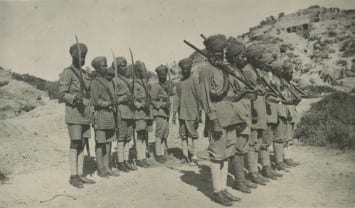

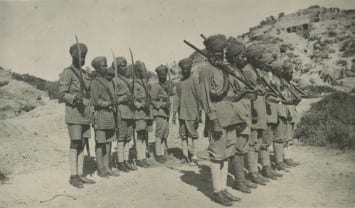

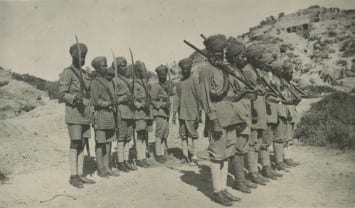

As Australians prepare to mark this centenary with great respect, to honor those who fell in the battle; the contribution of Indian troops in Gallipoli is also being remembered. They comprised Gurkha, Sikh battalions, and thousands of mule drivers who literally “moved” the British forces and their allies; but their vital contributions to the Gallipoli campaign have been overlooked largely. Australian historian and researcher Prof Peter Stanley is about to change that with his latest book, “Die in Battle, Do not Despair, The Indians on Gallipoli 1915.”

There were at least a dozen Indian-Australian soldiers who took part in WW1 as Anzacs — meaning they enlisted as soldiers in the Australian Imperial Forces but none of them took part in the Gallipoli campaign, since they joined the AIF after 1915. Even with that being said, their names are inscribed at the Australian War Memorial in Canberra, and they are paid homage to as Anzac troops.

The one who came back

A private collector in Canada has preserved two medals awarded to private Ganessa Singh, described as an Indian Anzac who returned safely back home to South Australia after completing his deployment in WW1. It was mentioned earlier that none of the Indian Anzacs actually fought in Gallipoli.

Historian Stanley has found that there were four Gurkha battalions, one Sikh infantry battalion (of 14th Sikh that suffered 80% casualties in June 1915 alone) and many thousands of Punjabi mule drivers in Galliopli. None of their personal experiences seem to have been documented. This may be attributed to the old saying that those who create history seldom have the time to write about it, or as Stanley believes: “Most Indian troops were either illiterate or if they did maintain any records, those haven’t survived.” Which is why their stories have never been told accurately, until now.

Stanley says, “To understand the Indian experience of Gallipoli, you must search the Anzac records – the diaries, photographs and letters of Anzac soldiers who wrote endearingly about their Indian mates”. He asserts that the close ties between Australia and India can be traced back to the landings at Anzac Cove, where Australians and Indians stood together resolutely, shoulder to shoulder.

When Stanley traveled to New Zealand, India ,and Nepal to obtain more records, he found that 16,000 Indian troops had fought alongside the Anzacs in Gallipoli, of whom 1,600 became casualties of war. His book lists the names of these Indians, predominantly Gurkhas or Sikhs, who were cremated in Gallipoli after they fell.

Trawling through the Anzac records, Stanley found multiple mentions of the bravery of an Indian infantry man named Karam Singh. Many Anzacs wrote about him with great awe, as he said to have continued to issue orders to his troops even after he had been hit and blinded by an artillery shell.

Stanley tells us that even the most famous Australian Anzac, John Simpson Kirkpatrick (popular in Australian folklore as Simpson and his donkey), used to stay with the Indian mule drivers in the battlefields of Gallipoli, because he preferred the fresh food they cooked over the bully beef supplied in the Australian rations. They also mention how Simpson’s enjoyed chapattis and freshly cooked curries, just two weeks before he himself succumbed to the war.

Letters sent by Anzacs show that they had the highest regard for the courage and professionalism of the Indian troops. One Anzac even sent a photo with his Sikh mate, which was published in the Sydney Mail in 1916 with the title “Best Chums”. It is remarkable that he introduced him to his family as “a mate”. “That picture truly stands out for me,” says Stanley, adding: “the true friendship between Indians and Australians can be traced back to the fields of Gallipoli — a friendship that must be commemorated in this centenary year”.

Fact File

April 25 will mark the centenary of the landing of the Australian and New Zealand (Anzac) troops in Gallipoli, for the World War-1 campaign.

Many regard April 25, 1915, as the day when Australia truly forged its national identity. At the centenary celebrations, contribution of Indian troops in Gallipoli is being remembered Indian troops comprised Gurkha and Sikh battalions, and thousands of mule drivers. Their vital contributions to the Gallipoli campaign has been overlooked largely Australian historian Peter Stanley about to change that with his latest book. At least a dozen Indian-Australian soldiers took part in WW1 as Anzacs.